Make sure you identify the big questions that define your characters

This is part one of a three-part series on Storytelling Tips. Also see:

• Part 2: Mind your language: Repetition, clichés and modifiers

• Part 3: Premise: What your book is really all about

What is the one ingredient — the Minimum Viable Product — shared by every bestseller?

A plot with more twists than a saltwater taffy machine? No.

Frenetic, kinetic action that leaves you gasping for breath? Nope.

Evocative descriptions that make the readers believe they’re actually there? Nu-uh.

You could have any or all of those and still have a total flop. What you need is a minimum of one character. Novels can survive almost anything their creators are willing to inflict on them. Books without twisty plots. Books without any physical action. Books set all in the mind. But what they can’t survive is an absence of characters.

Actually, is a single character enough? No, not really. A character gives you a novel. But you want to write a bestselling novel.

So you need at least one character your reader can relate to. And that word — relate — is very important.

Relatable is the key

Relate to a psychopath? What kind of person do you think I am?

We’re writers, OK? So words matter to us. Then let’s begin with a simple but crucial distinction.

It’s the difference between characters who are likable and characters who are relatable.

Read enough online reviews and eventually you’ll come across readers who felt none of the characters in the book they’d just finished were “likable.’’ Now, they may genuinely feel that unless they like the characters in the books they read, they can’t enjoy them.

But it’s far more probable that they’re using a linguistic shortcut (which they’re allowed to, not being writers).

Is Hannibal Lecter likable? Or The Girl on the Train’s Rachel Watson? Is Mr. Darcy? Or Captain Ahab? Dolores Umbridge? Holden Caulfield? Or Scarlett O’Hara?

I’d suggest no. They’re really not. Cannibalistic, alcoholic, haughty, obsessive, sadistic, cynical narcissists, perhaps, but not likable.

Yet these are principal, or at least important, characters in some of the world’s most popular novels. How come?

Because they’re relatable.

We get them as people. We recognize them. Maybe we even secretly recognize a little bit of ourselves in them.

Some characters are so bad that readers love to hate them. And that in itself provides a strong motivation to pick up, and keep reading, a novel.

People like Hannibal Lecter and Rachel Watson start off as antiheroes. They may even finish as antiheroes. But because we can empathise with them, we stick with them. We don’t ever really like them, but that doesn’t matter.

So what does matter when you’re creating the characters who will populate your novel?

What makes a character relatable?

Relatable characters behave in ways that we can imagine ourselves behaving. They possess traits that we can imagine ourselves possessing. They’re not necessarily pretty — they traffic in envy, murderous rage, lust, schadenfreude — but that’s the point.

If they only have traits we see in other people, we may be able to understand them, but we don’t care about them. Our reaction is more likely to be, “I have no idea what motivates her to behave that way. So I’ll just avoid her.”

You’re walking down the street, earbuds in, listening to a motivational podcast by a famous blonde actress. Ahead of you, a young woman is pushing a stroller with two toddlers holding one side of the stroller each.

Suddenly she turns and lashes out, catching the right-hand kid a backhanded blow across the ear. He starts bawling.

What a dreadful woman, you think. There’s no need for that. Such a bad mother. I should really call Child Services.

This character, we’ll call her Vicious Mom, is definitely not likable. And she’s not relatable, either. You’d never hit your kids like that. And in public, too. Tsk.

Now rewind the scene and this time take out your earbuds. Pay attention to what’s in front of you.

The baby in the stroller is screaming. A nerve-jangling screech that sounds like it started a while back and isn’t going to let up any time soon. The little kids are sniping at each other and whining.

“You’re a booger-face.”

“You’re a booger-face!”

“Mom, I’m hot.”

“And I wanna ice cream.”

The woman sighs. “We’re ten minutes from home, OK?” she says. “Let’s just get inside and we’ll all have ice cream, and I’ll put the fan on.”

“I want one now!”

“I need to pee.”

“I hate you.”

She turns. A dark bruise covers her right eye, extending halfway down her cheek. You missed it the first time because you weren’t paying attention.

“I hate you too. I wish you were dead!”

“Shut up!” she screams. “Just for one Goddamn second! He’s bad enough without you two getting in on the act.”

And she lashes out.

The violence is just as shocking. Just as unpalatable. We don’t like her any the more. But somehow we can relate to her. She’s being abused by her husband. She’s under stress. She’s probably dreading going home, even though she has to.

Maybe you think about catching up with her and telling her about a hotline for abused women.

We relate to her because we have context. We see not just what she does but why she does it.

Or, have her go home and stab her drunk and violent husband in the belly with a cook’s knife. Spill the bastard’s guts all over the immaculate kitchen floor and have her slip and slide in the mess, a grin breaking out on her bruised face.

Have her take the kids round to a neighbour and then go a-huntin’, looking for other abusers to whom she can teach a final, bloody lesson. Title your book, I’m Not Your Little Woman Anymore.

What drives your character?

In the example above, the young woman is motivated initially by fear. Then anger. It’s incredibly important to understand what drives your protagonist. And their antagonist.

The serial killer wants to keep killing women who remind him of the fiancé who jilted him. The cop on his trail burns with a desire to catch killers because his own mother was murdered.

The dog walker desperately wants to meet a man she can fall in love with. The widowed veterinarian needs to move on after his wife died in a boating accident.

How do they deal with these motivations? Are they passive, just waiting for something to happen? Or do they have agency? Searching, struggling, resisting, striving? How do they react in social situations? Are they outgoing? Happy-go-lucky? Or withdrawn, shy, self-contained?

When they get knocked back in their quest for fulfillment or a goal, how do they deal with it? With fortitude? Weary stoicism? Do they get angry? Do they plot and scheme? Enlist the help of friends? Cut deals? Go to the cops? Run?

These are the big questions that define characters. And they are way, way more important than eye-color, hairstyle or preferred brand of underwear. Answer them and be consistent in the way they inform your characters’ actions and your readers will reward you with attention, engagement, positive reviews and repeat purchases.

How to better understand your characters

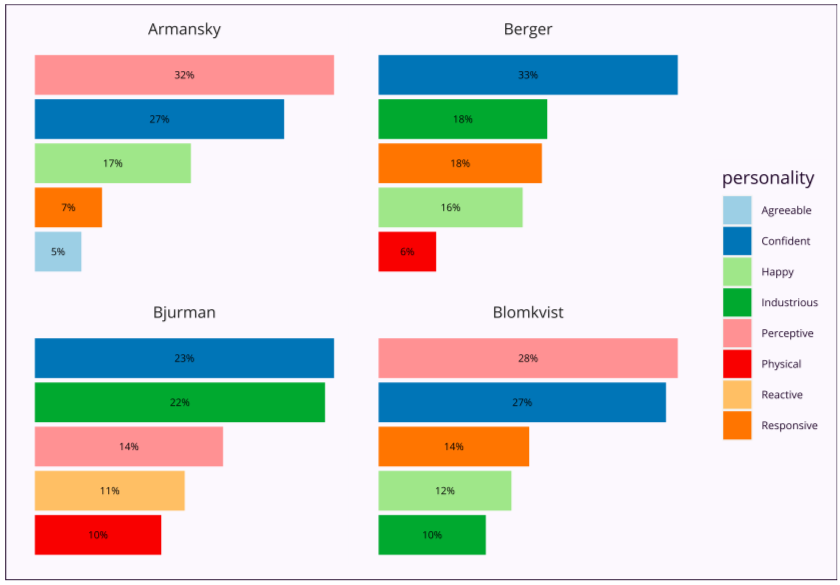

Marlowe, the artificial intelligence from Authors A.I., can help with this part of the writing process. Marlowe analyzes your characters’ actions — what they say and what they do. From these, she constructs thumbnail sketches in the form of bar-charts that illustrate their principal traits.

Using words like confident, perceptive, unsettled, physical and happy, Marlowe shows you how your characters are likely to be perceived by your readers.

As with so many elements of novel writing, what a novelist thinks she’s done may not accord with her readers’ opinions. The hero of her novel is supposed to be a rugged outdoorsy type, the sort to build log cabins with nothing but a hand axe and a Bowie knife. But the hero’s actions, speeches and inner monologues suggest someone altogether more bookish and introspective.

Maybe it’s time to take a second look at this character and give them a more active, physical role in the book. If she can link it up with some of the themes of the book discussed here, that will enrich the reader’s experience, both of the character and the novel overall.

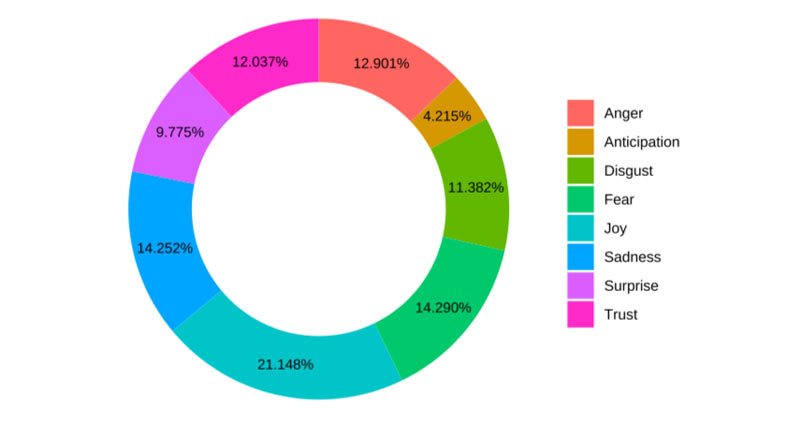

Marlowe gives us a second chart that offers an even deeper take on the way our characters shape our novels, and our raiders’ experience.

Professor Robert Plutchik of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine devised a classification of eight primary emotions. These are anger, fear, sadness, disgust, surprise, anticipation, trust, and joy. Marlowe uses Prof. Plutchik’s classification in an emotional color wheel to show authors what percentage of their novels conform to one of eight fundamental emotions.

Using the color wheel is a nuanced process. Nobody would suggest you rewrite a book using a single tool. But it’s a useful guide to the overall emotional tenor of your novel.

If one emotion dominates and it ties in with the flavor of the novel you’ve written (or think you have), all is well and good. But if it feels at odds with your book’s theme, or feels too strong to beta readers or a developmental editor, now’s your chance to take another look at your manuscript and see where things are getting too hot, cold or even (hush, whisper it) meh.

Could you fall in love with a killer?

Readers come to novels for many reasons. Escapism. Insight. Thrills. Entertainment. Even learning. Yes, learning. Because one of the ways we make sense of the world is through the stories we read. And chief among the insights we hope to gain are those that lead us inside other lives.

Get your characters right, make them relatable — whether they’re serial killers or cereal millers — and you’re one step closer to that bestseller flash on your book jacket.

Interested in checking out the free version of Marlowe? Check the Marlowe Basic page or compare the different plans.