Andy Maslen and Alessandra Torre discuss how to create complex characters for your novel.

How to create characters your readers will love (or love to hate)

Conflict is at the heart of all great fiction. Without conflict there is no story. “The cat sat on the mat is not the beginning of a story,” thriller author John Le Carre once said. “The cat sat on the dog’s mat is.”

For there to be conflict, we need two ingredients. Possibly the only two ingredients any successful story has ever needed, from Ovid’s Metamorphoses to the latest Jack Reacher pot boiler. A protagonist, or hero. And an antagonist aka the villain.

Your hero might be any kind of person, depending on the genre in which you write. A veterinary nurse. A biker. A country squire. A small-town sheriff. A vampire. A cat. A former Special Forces operative.

What’s wrong with being a good person?

Now comes the fun bit. Imbuing that hero with a set of characteristics, formative experiences, physical features, psychological traits and all the other bits of baggage that go to create a truly rounded character.

So, your veterinary nurse might be kind, in love with animals, quiet, dutiful, loyal to her boss, have a cute dimple in her right cheek when she smiles.

Your former Navy SEAL is tough, good with weapons, disciplined, built like a tank, skilled at evading capture and possessed of a rugged and stubbled jaw.

So far, so meh.

Boooring!

Flawless people are not characters. They’re one-dimensional. They’re caricatures. They’re paragons. And paragons are boring. There. I said it. Sorry.

You may have met people like this in your own life. Homecoming queens, star quarterbacks, head girls, perfect sisters, loving godfathers, always there for others, regular givers to charity, shoulders to cry on, rescuers of kittens out of trees.

Flawless people are not characters. They’re paragons.

And how do these people make us feel? Come on, you can say it, I won’t tell anyone. No? Let me, then.

We start looking for flaws. Something – anything – that would bring them down to the level of mere humans. You know, like us.

On the page, paragons lose their luster fairly quickly, too. An ex-SAS member who wins every fight, hits the target with every round and defeats the terrorists without sustaining so much as a scratch leaves us with little to wonder about.

As each new challenge, or opponent, comes into view, there’s zero tension. Because we know he’ll win. Every time. And where’s the fun in that?

Introducing the vulnerable hero

Now imagine a different kind of protagonist. He’s still ex-Special Forces, but he’s short-tempered. No, make that hot-tempered. Oh, and he carries the burden of a comrade’s death in combat. Which gave him PTSD.

In moments of heightened emotional stress, his PTSD threatens to overwhelm him, leaving him vulnerable.

Now, there’s doubt. He ought to triumph. (And, given that this is a series of books, we pretty much know he will.) But not before experiencing that vital ingredient in good stories. A setback.

How I do it

I’ve written novels in three series. One features just such an ex-SAS guy. Gabriel Wolfe has all the attributes you might expect of a former member of an elite fighting unit. He also suffers from PTSD.

Another series focuses on a detective, Stella Cole. She lost her family in a hit and run incident. Her grief triggered a form of psychosis that led her to embark on a bloody trail of murderous vengeance.

The third follows a detective who works in my adopted home town of Salisbury, England. Ford had to leave his wife to die after a climbing accident. He bears the guilt heavily and it leads him to be over-protective of his son.

All three protagonists are recognizable types and possess a great many virtues, from love of country and belief in British justice to fierce loyalty to friends and being a pretty decent blues guitarist.

But what brings them off the page and into my readers’ minds as fleshed-out, three-dimensional people is that they are a confusing and sometimes confused mixture of virtues and flaws.

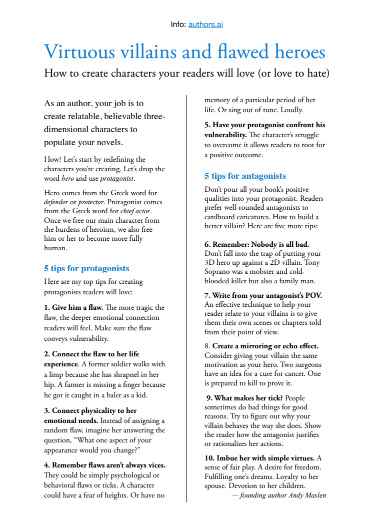

At this point, I want to suggest a way to get into the right mindset for creating believable central characters. Drop the word hero, which comes from the Greek word for defender or protector. Instead, use protagonist, which comes from the Greek word for chief actor. Once we free our main character from the burdens of heroism, we also free him or her to become more fully human.

Does your hero have any flaws?

So, what flaws might we give to our protagonist? A good place to start is the holy books of the world’s major religions. For simplicity, I’ll take the Bible. The seven deadly sins give us some pretty fertile ground for muddying the waters of our protagonist’s virtue.

Pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth: just one would be enough to add some shades of grey to your protagonist’s character.

But we can be far more inventive. Especially once we ditch the word “flaws” and use “vulnerabilities” instead. And this is where you can engender your reader’s sympathy for your protagonist.

How far would you go to save your child?

Let’s take our Navy SEAL and give him a 10-year-old daughter. He loves her to death.

Now let’s have the bad guys kidnap the daughter. They say if he wants to see her alive again he’d better assassinate the president.

You could take the reader down a mazy path of self-doubt and moral brinkmanship as the SEAL gets as far as lining up POTUS in the sights of his sniper rifle.

Remember our veterinary nurse? In my mind, she’s called Becky. Sweet kid. Only 25 and doing the job she’s wanted to do ever since, as a kid, she rescued a raccoon with a busted leg. She’s also in love with the practice boss, who only has eyes for another nurse.

Because she’s so much younger than the other nurses in the practice, Becky is insecure and worries constantly she’s not good enough. One day, in an effort to boost her own self-confidence, she posts a picture on Instagram of her with a pet cat that somebody else in the practice saved.

The other nurse is furious and gets Becky sacked. Now how can Becky win her job back and the heart of the senior partner?

When I think of my readers reacting emotionally to what my protagonists do, I picture them not giving an unbroken series of air punches like a tennis player winning Wimbledon. All, Yes! You nailed it!.

Instead I want them covering their mouths, their eyes wide with shock or dismay. “Nooo!” they cry through slitted fingers. “Don’t do it!”

Because without that emotional engagement, our stories will leave our readers cold. It’s a bit like watching a trained sniper visiting a fairground shooting gallery.

‘I’ll win the prize or buy you a Mustang’

If the carnie has oiled the spindles on which the tin targets sit, zeroed the sights at 15 feet and cleaned the barrel with a little gun oil, there’s no tension.

The protagonist, let’s call him Mike, draws a big crowd and makes a wild boast. “Watch this, folks. Ten rounds, ten targets down. Or I’ll buy this guy a new Mustang.”

He takes aim, squeezes the trigger and pow! Down goes the first target.

Authors need to rig the shooting gallery.

Nine more times Mike looses off a round and nine more times the tin targets fall. He walks off with a teddy bear the size of a baby grizzly. The crowd disperses. Eh, so what?

Now let’s rewind and have the carnie be a crooked example of the breed. The 10th target is soldered onto its spindle. Not only that, he whacked the front sight with a hammer.

Mike takes aim and just clips the first target. He realizes what’s happened and deftly adjusts his aim and pins the next eight targets. But the tenth stays upright. The crowd gasps. The carnie starts browsing Ford’s website on his phone.

Our job, as writers, is to rig the game just like the carnie. Not fatally, unless you’re writing noir with a disposable protagonist. Just enough to give them a rough ride for a couple of hundred pages.

Enough about heroes, what about the second player on the stage, the villain?

Meet the virtuous villain

Straightaway, I’m going to follow up my earlier suggestion about the words we use to describe our main characters. I want you to think about the villain as the antagonist (from the Greek for opponent or rival).

Yes, one of the English meanings of antagonist is villain, but that leads us down a path just as treacherous as that offered by hero. If we create a villain, then it stands to reason they will be villainous.

But now all I’m seeing is a top-hatted fellow chortling as he ropes a squirming girl to the railway tracks. Or a mustached bandito with ebony-handled six-shooters, killin’ innocent ranchers just for fun.

Two-dimensional villains are just as useless in fiction as two-dimensional heroes. Little more than pressed tin targets in our fairground shooting gallery. Our readers have no illusions about them. They’re going down and the only question is when, and how?

No. Let’s give them a fighting chance. Right up to the denouement.

Nurse Becky’s love rival is a competent veterinary nurse who has spent her life saving people’s beloved pets. OK, so she’s a square and she’s making a play for the senior partner. That’s not a crime, is it?

SEAL guy’s opponent is a domestic terrorist, but he loves his country, just like the SEAL. What’s more, he also had a 10-year-old daughter, until she was shot by a maverick CIA officer.

Nobody thinks they’re the villain

I looked at the bad guys in my 10-book series about ex-SAS member Gabriel Wolfe. Here are their main motivations for taking the actions they do. As they see it.

- Hatred of oppressors

- Disdain for bourgeois decadence

- Duty to her country

- Vengeance for her father’s murder

- Lifelong fight against communism

- Defeat of a more powerful enemy

- Restoration of lost honor

- Loyalty to party

- Desire for a fairer society

Now, any one of those could just as easily be applied to a hero. And that’s not an accident. Or sloppy plotting on my part. Because, and I think this is my major insight into the antagonist’s mindset …

Nobody thinks they’re the villain. Especially the villain.

Three of my favorite fictional villains are psychopathic mass murderers. Dexter Morgan, Tom Ripley and Hannibal Lecter.

Each man’s actions are despicable, shocking and grotesque, and far, far beyond any normal person’s conception of reasonable. Yet each has a role in which he gives a heroic turn.

Sympathy for the devil?

Let’s take just one of them. Thomas Harris’s brilliant creation: Dr. Lecter. Whether you prefer the literary version, or those played on screen by Brian Cox (under-rated and for my money scarier) or Anthony Hopkins, Hannibal Lecter is charismatic, cultured, a good son and a skilful and accomplished doctor among many other accomplishments.

Yes, he [spoiler alert] kills and eats people. But often they are rude, boorish, violent individuals who, to use a playground term.

On a technical level, what Patricia Highsmith, Thomas Harris and Jeff Lindsay do is to tell their stories in part from their psychopath’s point of view. And as readers, we find it difficult to remain objective about the POV narrator. We tend, as a default, to relate to them.

Of course, this is manipulative, by the author as well as the narrator. Because as I said a moment ago, the protagonist doesn’t see themselves as a villain. They frame their actions as entirely reasonable, given the provocations, and the circumstances in which they occurred.

Is virtue wasted on the good?

Writing engaging, emotionally satisfying, best-selling fiction requires us to create characters to whom our readers can relate. Just like in real life.

The people with whom we form the deepest connections are not perfect. Far from it. We love our best friends despite their flaws, not because they don’t have any.

We root for athletes who overcome great odds, not those who seem to cruise through life, arriving on the winner’s podium as if by right.

We love underdogs, not overdogs.

The same goes for villains. J.K. Rowling understood this when she created Voldemort. Yes, a thoroughly nasty being with serious anger management issues, but the reincarnation of poor, yearning Tom Riddle, bullied by Harry’s own father.

You must give your hero a worthy adversary

And this is my point, really, and final piece of advice.

Heroes can generally take care of themselves. The gods, in the form of their author creators, imbue them with more virtues than any one person needs.

It’s the villains we need to look after. Spend at least as much time creating a rich inner life for them as you do for your hero. One in which they can tell themselves that their actions, however bad, are justifiable.

Because, if we’ve devoted time and energy to creating a relatable protagonist, let’s at least provide them – and our readers – with a worthy adversary.

Want to check how your characters size up?

When I need an objective review of my work in progress or finished novel, I turn to Marlowe, the fiction-savvy artificial intelligence from Authors A.I. The character analysis gives you an overview of their behavior throughout your work. But as to whether you’ve created realistic, relatable heroes and villains? That’s up to you.

I’ve created a top 10 list of things to keep in mind when you’re creating your protagonist and antagonist. See my new handout: 10 tips for creating flawed heroes and virtuous villains.

GET FREE A.I. REPORTS