The art of writing is a complicated web of tricks and processes picked up from a variety of places and unique to every author. Some swear by outlining while others turn up their nose at its structure. Others only write by hand, some dictate, while others use old-fashion typewriter-style keyboards because the metallic clicks spur their creative juices.

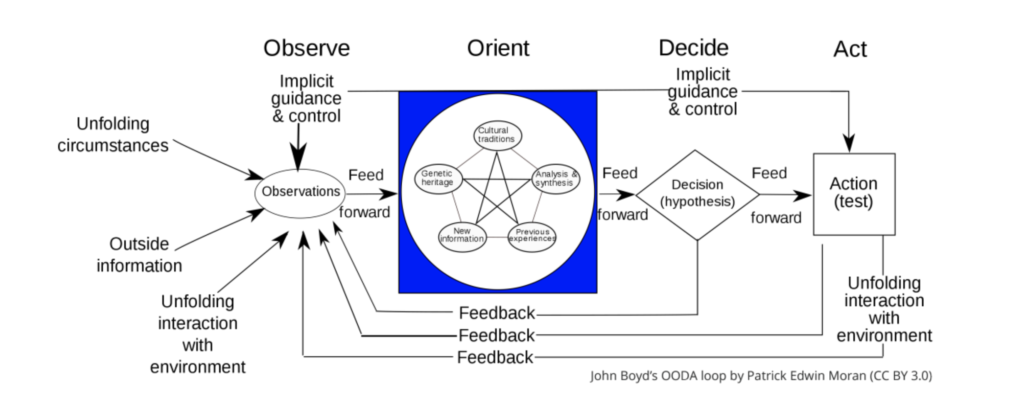

For our most recent First Draft Friday, I sat down with veteran authors Judith Lucci and Fiona Quinn to learn their method of writing characters and developing scenes. They pointed to something called the OODA loop. Developed for military use, this decades-old methodology can be used in fiction as a four-step approach to character decision-making. It stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. In our live chat, Judith and Fiona describe how its four components can be applied to writing great fiction characters and scenes.

Here is a one-page handout that summarizes how to use the OODA method in your fiction writing.

The OODA loop breaks down as follows:

Observe

1You write what’s happening around the character. It might be unfolding circumstances, interaction with the environment, new information, etc.

What in the scene would your POV character observe amid the action? For example, if your character is a physical therapist, she might take in the robbery suspect’s limping gait. A police officer might observe the suspect’s hand movements.

Orient

2This is the most important step in the process. Consider aspects of the character that would shape how they observe a situation. If you have several characters in a scene, each will have their own way of perceiving, deciding and acting. If you have a group, the orientation is the place where the conflict lies.

No two people will have the same orientation. Factors might involve age, ethnic heritage, education, gender, mental acuity, temperament, life experience, health, current relationships and so forth.

Decide

3This could be a conscious decision or reflexive reaction. Now’s the time to walk the reader through the thought process—why did your protagonist decide to do A over B? Was it a hard decision? What stood in the way? What was the key factor in making that decision? Morality? Greed? Survival?

Act

4The characters now act and change the external dynamics or emotional valence of a scene. Their actions must result in a change. They’ll be following the same process over and over in an ongoing loop.

There! That completes the OODA loop. For a full breakdown and discussion, be sure to watch the video chat (posted above).

If you’re interested in reading Judith or Fiona’s books — or learning more about the authors who appeared in this video — their information is below.

And if you’d like to watch more author videos, or join in future live events, visit our First Draft Friday page.

Our author guests

Fiona Quinn is a five-time USA Today bestselling author, a Kindle Scout winner, and has been listed as an Amazon Top 100 author in: Romantic Suspense; Mystery, thriller, and suspense; Mysteries, Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror.

Quinn writes smart, sexy suspense with a psychic twist in her Iniquus World of books including: Lynx, Strike Force, Uncommon Enemies, Kate Hamilton Mysteries, and FBI Joint Task Force Series. She writes urban fantasy as Fiona Angelica Quinn for her Elemental Witches Series. And, just for fun, she writes the Badge Bunny Booze Mystery Collection with her dear friend, Tina Glasneck. Find out more at www.fionaquinnbooks.com.

Judith Lucci is a Wall Street Journal, USA Today and Amazon bestselling author of fast-paced, riveting thrillers that offer readers believable drama, memorable characters and true suspense. Her books are described as “unputdownable.”

Judith was born and educated in Virginia, where she holds graduate and doctoral degrees from Virginia Commonwealth University and the University of Virginia. She is also the author of numerous academic and health-related articles and documents. She loves to communicate with her readers at www.judithlucci.com.

GET FREE A.I. REPORTS

Transcript of our conversation

Alessandra: Hi everybody. I’m Alessandra from Authors AI. This is First Draft Friday. I’m so excited to be joined today by Judith Lucci and Fiona Quinn. These are two rock star authors that have more than 40 best sellers between them. And today we’re going to be talking about a really cool technique that you can use to build amazing characters and plot lines. I was reading over the handout, which I’ll provide a link to in just a moment before we begin. I’m so excited to have you both on First Draft Friday to share this really interesting, I guess, characterization technique. I don’t even know the right word to describe it, but I’m going to turn the mic over to you guys. For those of you who are watching live, feel free to comment and ask questions and it’s going to be a jam-packed half-hour. But if we can answer any of your questions, we’re going to get to as many as we can. So I’ll turn the mic over to you guys.

Judith: Okay. Thank you so much. Hi guys, I am delighted to be here. My name is Judith Lucci and I write medical thrillers, psychological suspense, and cozy mysteries. I penned the Women of Valor World and my three series that are currently part of that world include the Alexandra Destephano Medical Thrillers, the Michaela McPherson Crime Series, and the Sonia Amon Medical Thrillers. I’m a USA Today and Wall Street Journal published author. In my other life, the one before writing that I think I worked less, I was a nurse who spent a lifetime in hospitals and medical care facilities in a number of countries around the world. And I am so happy because sitting here right next to me is my amazing friend Fiona Quinn.

Fiona: Hi everyone. Yes, Judith and I met when we were starting our writing careers and she has been a stalwart friend and I really appreciate all of her insights that she shares with me. Like Judith, I have a bunch of degrees in my background, but for the sake of today’s talk, I’m going to be wearing my psychology hat. I have a master’s degree in counseling from the Medical College of Virginia. As a writer, I’m a Kindle Scout winner. I’ve been on the USA Today bestseller list five times and I’ve been an Amazon top 100 mystery thriller suspense author. For the most part, I’m writing action, adventure, romance. I have 20 books into my Iniquus World which is ex-special forces where I use my fighting background, my survival skills, and my emergency management experience on the pages of the book. And from that background, I learned about OODA loop. OODA is spelled O O D A. OODA loop, which is the subject of today’s talk. So OODA loop is one of the techniques that I’ve always applied to my writing to bring my readers along on the same ride as my characters.

Judith: So we’re going to be talking about OODA loop today, with a special emphasis on the importance of perception and the use of our senses when we’re developing characters in scenes. We will have a handout as Alessandra just told us for you, so the major takeaways will be on that handout. So we’re going to go through this and we’re hoping that it’ll be useful to you as you begin to work on your manuscript. Fiona, since this is sort of like your model, why don’t you introduce us to it?

Fiona: Okay. So for those unfamiliar, with the concept of the OODA loop and those letters stand for observe, orient, decide, act. The term OODA loop was coined in the 1950s by Colonel John Boyd. He was a fighter pilot at the end of the Korean War, and he was piloting an F-86 and they were wondering why the pilots were not being as effective on their mission. So he took it upon himself to look into that and he realized that every pilot came to the mission with a different way of observing, orienting, and then deciding, and that impacted what actions they took. So he looked at the precipitant to action in the OODA loop. And as Judith and I will be talking about today, note that if you’re a new author, you’ll find that using OODA loop gives you and your characters added dimension. If you’re an advanced author, this might be a new way to frame some of the techniques you already use and also be a way for you to reimagine a scene if you get stuck. Ask yourself, okay, what is my character experiencing through their senses? And how does that create a feedback loop that determines their next actions?

Judith: Okay. So the first step as Fiona said is to observe what’s happening around the character. This is really important because it orients us and eventually our readers to the scene and it helps us decide what to do next. They’re often unfolding circumstances, for example, the weather, which we’re experiencing here now with Hurricane Laura. The time of day, perhaps a new sound, maybe some outside interference, a helicopter. Anything that your character may hear will perhaps unfold an interaction with his or her environment. For instance, think about a gunshot that might occur. So because observation is so important and sets the stage for us as writers, we’re going to introduce the beginning of the action loop with the memory. It could be a thought, an ‘aha’ moment as part of a conversation, or something that is generally, almost always sensory-based. The phone rings, the sound of that phone spurs your character to move within the scene. Perhaps the person on the other end of the phone is hysterical, or maybe even uncertain. Maybe it’s a cry for help.

In my first novel, Chaos at Crescent City Medical Center, I have a Mardi Gras scene that illustrates these concepts. Now, if any of you guys have actually ever really been to Mardi Gras, you know, that you’ll see observations there and orientations like you’ve never experienced before. But we’re not going to talk about those completely today. But here’s a quick scene from Chaos. The pungent smell of Cajun spices permeated the February New Orleans air with only one week before carnival the French quarter blazed with activity. Ornate iron balconies bode beneath the weight of dozens of people pressed closely together for a better look at the street. Being up on a balcony during Mardi Gras was prestigious and it gave one an immense sense of power and control over the crowd. People in the streets would do just about anything for a Mardi Gras throw. A string of plastic beads or an aluminum doubloon. So you can see in this scene, how I’ve described what’s actually going on in the environment there, in that Mardi Gras moment. And then I move on with the next part of the OODA loop, which we’ll talk about in just a few minutes. But you can see that the reader can visualize and they can hear and they can smell, and they can actually see what’s going on in that scene. Would you agree, Fiona?

Fiona: It would and the interesting thing about using that Mardi Gras scene is that it is so sensory-rich, right? The sound and the smell and just the vibration of the whole area. So when you are writing that your character is going to have to make those observations, but they’re also going to orient one or two. The ones that are most important. So we know that our brain absorbs millions of pieces of data all time, but it filters down and to give you an example. Your eyes can see your nose all the time, but your eyes tell your brain that the nose is not there and not important. So we never see our nose, but it’s there, it’s right there in our visual field. So we have the observation. That’s the thing that catches the brain, right.

When you are making the decision about orienting your character. So, in your observation to orientation, you have to consider each character and what they would find as important. If you have several characters in the scene, each one will have a different observation and a different orientation to it, leading to a different decision and a different action. So I think I’m going to talk, Judith can you remind me, I want to talk about a scene in a minute. But let’s talk about some things about your character that might change their observations and their orientations. It could be heritage and cultural traditions. It could be previous experience, educational training, gender, job history. It could be mental health. For example, researchers have identified a gene that amplifies the feeling of endangerment, and people with this gene it’s believed, they’re in the beginning of a scientific study of this, will experience the events with more hormone actions that derive from the anxiety, their reactions to the situation. They’ll be secreting more adrenaline, more cortisol which will affect, you know, their eyesight and their hearing acuity, their physical ability.

So when you’re writing the scene, if you’re like me, your character wears glasses. If I wake up in the middle of the night, I’m hunting for those glasses because without them I can’t see. And that would change not only would I observe how I view things, but also how much anxiety I feel around not being able to see clearly if there’s something that needs my attention. This might also even be something like hearing. I’ll give you an example from my life. I’m a homeschooling mother of four. So I raised four kids. Sometimes they needed to be separated out. I could put four kids in four different rooms and listen to their activities and know if they were on task or if a mom needed to go and intervene. At night, because my husband traveled, I was the only adult in the house. And so I had a heightened hearing acuity, even a small noise would spring me from my sleep because I knew I was the sole adult who is in charge of an infant, a toddler, and two little kids. You know, that I had to save them from the fire, the burglar, whatever happens, you know. So I was always primed.

My husband on the other hand was you know, traveled alone. He didn’t have to weigh in with anybody else at night. His perceptions closed in on him because, in a hotel, he didn’t want to hear other people. He didn’t want to be sprung from his sleep. So we had completely different abilities to hear and perceive because we trained that into ourselves. Judith, I was reading in your new Witch book where you were illustrating perception and observation. Can you share an excerpt from that?

Judith: Sure. This is another example of sensory observation. This is a new series for me. It hasn’t been published yet. The title of the book is “Seer of Evil,” and the main character is Maura and she is a psychic witch and an investigative reporter for the Times Picayune. Blinding pain and bright lights seared my brain. I covered my eyes and grabbed my head to stop the agony. It didn’t help. Stumbling from my bed, I grasped my bedpost for support and made my way into the bathroom. I bend over, turned on the water, and bathed my face. I was so weak. I had to rest my arms on the sink. A moment later, I was sickened by the stench of rotting, flesh and dead fish. A dampness permeated my body. The smell of death was in the air. And I knew that he was here in my house. But who was he? Who was this man in the mist? That I did not know and it terrified me. What did he want? Why did he want me? And most of all, why had he invaded my life and my dreams?

So, as you can tell, Maura has observed some stuff here that she really cannot explain. And she’s clearly in pain, you know, but she’s in psychogenic pain and she’s also in physical pain. And I can feel her emotion when I read it. I’m really hopeful that my readers are going to feel that same emotion. So, you know, picking your sensory words in making those descriptions are very, very important I think when you’re setting the scene. Fiona, you’ve got an experience that encompasses several authors of several characters.

Fiona: Yeah. Thanks for reminding me. Just going back for a second, I’ve wanted to say that disorientation is also an orientation and you disoriented your character so that your readers are also asking those questions. And when you ask your readers’ questions, as if they’re part of the scene, then you’re pulling those readers along with you. It’s a psychological trick that counselors use. So what you want to do is you’re taking them along that same path with you and that disorientation and asking the questions and hoping to gather more information through observation are really interesting craft tricks for authors to use. So when that was a single character in a scene.

So let’s look at a scene where we have different characters who observe and orient and then decide and act in different ways. I’m going to put you in a gas station. You’ve gone in to pay for your gas. You are buying yourself a chocolate bar. You’re up there paying your money and a guy comes in with a gun. Skipping forward, the police are asking the three people who were in there, what did you see? What did you do and why did you do it? So, for example, if we had an artist in there, the artist might remark of their facial features trying to remember them so that if the guy got away and the cameras weren’t working, that she could draw a good rendering of that image for the police and they could go after him. Or she might have through the way she has observed and drawn faces in the past, might notice that that emotion that is on the face is pain and she may decide, well, I think that what he did was him coming here to get money for drugs and I’m going to give him some money. I’m just going to give him my wallet so that he knows I want him to get that pain relief and he won’t point the gun at me.

A physical therapist who is in there might’ve noticed that when he came in, he was dragging his leg and he had a difficult gait. She knows from what she’s observing that he won’t be able to chase after her. So as soon as the gun is pointed elsewhere, she dashes out the door and around the corner. So she’s not in the trajectory of the bullet, knowing that he will not chase her down. If you had a soldier in there she might not be watching the man’s face at all. She might have been leaning on her training to look at the hands because the hands are where the danger lies. As the criminal moves the gun to the side, and he is sweeping over everyone trying to be menacing and subdue them the soldier waits her turn to leap in and grab hold of the slide on the 1911. Drag the gun over, so it’s pointing at the back wall and sure the guy gets the shot off but because of the soldier’s training, she knows that the next round can’t chamber. She slams him with her knee into the grind, puts him on the ground and that’s how that soldier took him down, right. So three completely different perceptions, three completely different ways of responding to a threat, but it’s the same threat.

Judith: And that directly goes back to what you had said earlier while the gentlemen developed the model, to begin with.

Fiona: Right.

Judith: So that’s just another really clear explanation of it. Well, now we need to talk about the physical act of decision-making because that’s another part of this model. If you think about it, when we make decisions, we have two ways in which we make them. We can make a cognizant decision which is based on, you know, a thinking process, hopefully. I certainly hope it is. Or you could have also a reflexive decision. Say, for instance, the baby’s falling, so the mother reaches out and her hand shoots out and she catches the baby in the blink of an eye. But what we want to talk about here particularly is why would your character pick one action or another? How do they decide A over B? So let’s think about this a little bit. Is it a really hard decision for them to make? Is it a very painful decision? What stood in their way? What are the objectives of that decision? What needs to happen? Is there a distortion of these people’s senses?

Certainly, when we go back to Maura and the man in the mist, her senses are distorted, to some degree. Do they have tunnel vision? Are they able to hear? What is the most important tool that they’ll be using in that decision? Is it based on morality or greed? Is it based on survival? Are these people habituated to making stressful decisions? In Fiona’s books, I know that all of her guys are Spec Op kinds of people, and they’re kind of used to dealing with situations. Maura, my character really isn’t because she’s an investigative reporter. So always remember that when your character is making a painful decision, there’s going to be an adrenaline flow there. You guys can remember the fight and flight, you know. And they can also be frozen because they can’t move or do anything and that would equate with a loss of function. So these are just a couple of ideas that you need to think about when you’re making a decision.

Fiona: Judith, I was just going to throw in there that it also has to do with the relationship. So for example, I’m trained in responding and I’m trained as a counseling emergency response person. So I’m trained to be in stressful situations. I’m trained to function with my first aid. And I can do that. I have done that. I’ve saved people’s lives. But when my kid is on the floor, I can tell you that my ability to struggle through that adrenaline to save my child is a very, very different experience. The soldier on the battlefield who’s around blood might be able to be just fine with that blood, but when he’s watching his baby being born, that might put him on the floor. He may just get away with that one. So you are not just assuming that your character and it’s really interesting and telling and has some depth to it. It makes your character more 3D when something is thrown into the mix that makes them act out of character, and then they are startled by their own actions or reactions.

Alessandra: And I think I deal with a lot of new authors, and I think if you’re a new author and you’re watching this, the other thing you need to remember is the instinct is to write how you would react in that situation. And you have to remember your character and their backstory, and however, you’ve built them. So I’ve seen a lot of new authors writing their characters behaving the way that they would react to that. But like you said like a Navy seal is going to react differently than a housewife mother who’s, you know, maybe never been in a stressful situation.

Judith: Yeah. It’s amazing. I mean, I spent many years in emergency rooms and the responses that you think you’re going to get, and boy, do you find out you’re really not going to get that response. So it’s a very individual type of thing and it’s a floating thing. It depends on what else is going on in the environment.

Fiona: It’s fatigue, hunger. I mean, how many of us have been angry at someone who didn’t deserve it? And it was a physical problem. So let’s see, we were talking about the differences between characters and the differences that they’ve observed, something you’ve seen, they’ve oriented based on who they are and what they’ve experienced. What they know. They’ve decided on the actions that they’re going to take to the situation. And then they’re going to decide and they’re going to act, and then what happens next is you start all over again. We are constantly making this loop.

Judith: Yeah.

Fiona: Sorry.

Judith: Yes, it is. It’s a circular motion. It’s a loop.

Fiona: One thing leads to another, and that’s how you kind of roll your character through the plotline. I’m going to, I think, give you an example of how a person can start a loop, and another trick, to craft a trick, is to start your character through a loop and then throw them for a loop by changing their orientation. Okay. So this is a story about Barbara who is called to reception. There’s a bouquet of beautiful flowers waiting for her. She’s all smiles. She’s excited. She’s happy. She beams, as she walks back to her cubicle, grinning and blushing, accepting her compliments and comments from her colleagues because these flowers must be from the guy. He is the guy. And now that he sent flowers, she knows, he feels the same way. So she gets to her desk, she puts the flowers down, she picks up the card and she gives the envelope a little kiss and then slides it out to read the letter. And she finds out it’s from the creeper who has been kind of hanging out in the lobby making comments to her. And he said, “You looked beautiful last night.” And she was at home. So she grabs the flowers completely reoriented, not only just reoriented, but it’s worse because it wasn’t like she got the flowers, she read the thing, she threw them in, she said, we need to call the police. It was, she had oriented herself to, oh, the guy feels the same way I do. I’m so in love. This is going to be great. We’re heading into our bliss, but no, instead it’s the exact opposite. So, taking your loop and playing with it a little bit is sometimes a lot of fun.

Showing your characters making mistakes in that loop helps us to understand the characters’ inner fears and their inner desires and also your character’s mindset. For example, that might have been the way that you told your readers for the first time that she had decided that the blind date from last night, that that guy was the one, and that was the way she conveyed that. And then we just smack it. [unclear 26:38].

Judith: Yeah. He really wasn’t the one.

Fiona: It wasn’t. It wasn’t him.

Judith: It really wasn’t him. Okay. But you know, when you write about a character, you know, who’s making a sensory observation don’t just use the words, ‘she saw him and he was a creep’. You know make it more sensual. Put some body sensations in there such as heat, or actually pull into play the sixth sense that people often have. Intuition is an incredible sixth sense that we use all the time. So don’t just say, you know, jazz it up a little bit, not just, you know, she’s tasted bile or whatever.

Fiona: Bile to the back of her tongue and everyone can taste it, right. Everyone’s had bile. Even the texture and the taste of bitter. Yeah. It’s very sensory.

Judith: Yeah.

Fiona: And I’m going to add in there, one of the senses that’s left out a lot is the sense of smell. And it’s often our first warning. You know, we smell the smoke. But it’s also one of those things that is psychologically the most profound. It’s the one that brings up a memory. And so you can use the smell to evoke a memory. Then you get to share a little paragraph or two about your character’s past which edifies the situation or where their mind is at, or where that smell took them to. Which might’ve been very different from the sensation they had before they opened the door and were enwrapped in the smell of chocolate chip cookies. So if I say they were enwrapped in the smell of chocolate chip cookies instead of saying, she smelled the chocolate chip cookies baking. What you get is the sense of a hug and you also get that lovely, warm, familial childhood goodness. That’s in there. And then you can step on that by making something bad happen. But for that moment, you’re smelling them.

Judith: Keep them guessing.

Fiona: Just fool your readers all the time. They think it’s going to be good, but it’s not. But I’m going to add in there and here’s another one that you can use because it’s a throwback to our ancient brains. That if you hand someone a newborn baby, one of the things they will do very frequently is to bend over and breathe in the top of the infant’s head. And that’s imprinting that child in the brain. You would never go to someone’s ten-year-old child and lean over and sniff their head. It’s just not done. But when they’re an infant, it is done all the time. And the next time you see it happen is when you have made a couple bonding relationship. So a husband and wife, but your character is newly in love. They’re in love. When they love each other as a couple, they will breathe in the other person. And if you mentioned that the person who’s reading may not get what that means. But their brain gets what that means. So it’s a little layer of something that will…So you will often see when my couples fall in love, you know, it because they’re breathing each other.

Judith: So I think that what we’re saying in so many words is that you really want to describe the scene so that we all know what’s happening. The reader knows what’s happening. Remember when we talked about Maura a little bit ago, we could sense and actually smell her fear. So consider using a lot of sensory actions when you’re writing. So when you’re standing at the sink, you know, the character could put their hands under the hot water, or they could slide across greasy pans. You know, anything to make your…

Fiona: Smell grass wafting through the window, right?

Judith: Yeah. Anything to make your reader be there with you and with that character because that is what is so critical about this.

Fiona: Right. So in the OODA loops.

Judith: It just takes practice.

Fiona: It does take practice. And when you’re doing things, you can kind of practice on yourself. What am I observing? How did I orient to that? I hear a car coming and wait, that’s not my engine. It must be someone coming up the driveway that I don’t know. I better go look out the window. And a decision is made and action is taken. So we talked about your characters’ backgrounds and their personality aspects and how that will affect a new mood. And that no two people and no two characters will ever respond to the same event in the same way. We have put together the main points of this talk on the handout we mentioned earlier, and we hope it helps. Thank you for coming and hanging out with us and talking about OODA loops.

Judith: Yeah. Guys, thank you so much. It was fun. We’ve just talked about it. It’s a simple action model that will assist new writers in expressing their characters in their emotions and will actually help you think through your scenes. So if you have any questions, you know, feel free to contact either Fiona or myself on our websites or here at Authors AI. We would be delighted to talk to you more, even though you probably don’t want that. But anyway, we had a great time. It was fun. Thank you so much guys, for listening.

Alessandra: Thank you both for coming. This was really fascinating. And do you go through this loop with every scene? I mean, not that you know, characters have to make big decisions in every scene. But is it pretty much from one loop to another, as you move through the book?

Fiona: So I’m just going to answer that for me. Because I’m trained in that. That’s when I was a counselor and I was listening to my clients, I would listen for those OODA loops. What do they observe? What were they oriented to? What were their decision and their action, right? So for me, it comes naturally. It’s something that’s part of my writing as a natural course because I trained myself to do that. And so with a little practice, that’s fairly easy. But there are also times when I come to a point in my scene, I know kind of where it needs to go but I’m not sure how to get it there. Or I feel like the reader might not understand this decision or this action. So I better orient the reader by giving them an observation or taking them along for the ride. I sometimes will go back and say, this is lacking a spark. And then I might try it add the OODA loop so I can get the reader there, or it can drive new thoughts. I get to know my characters that way. They surprise me. I’ll be typing something out and my characters will always surprise me with their depth and their three-dimensionality when I apply this.

Judith: For me, I think that the more you write, the more it almost happens automatically without you deliberately looking for each letter in the OODA loop. I do think though that a special use of this model is if you have a problem scene. A scene that’s very difficult for you to write. That you’re just really not getting it. I think this is a wonderful way to refine that scene and to go back and to make sure that you’ve done or what your character has done and you, the author has done, what needs to happen in that scene. So it’s great. It’s a great little model. Anybody can use it. It’s not scary. So that’s important.

Alessandra: It’s not scary. Before you came on and explained it, I was intimidated because it sounds fancy and complicated. But it was really great to hear from both of you. And I’m really excited. I wrote down a few notes, like sensory actions, I realize as Judith was talking, I don’t use nearly enough sensory, like what my characters are touching and feeling. I think I’ve just skipped for my last 20 bucks. I need to…

Fiona: It’s really important, especially if you’re having a lot of dialogue, you can just orient your reader if they don’t get a periodic reminder of where you are. So you don’t want to keep going, ‘in the living room, in the living room’. So you would say, you know, she moved over to the couch and pushed the cushions to the side or threw the cushions on the floor next to the dog. You know, just little sensory things that reorient the direction, or, you know, the sunlight was hitting her in her eyes so she moved to the side. Whatever it is, it reminds your reader where they are. So they know who’s speaking? Where they are? And that gives them a sense of equilibrium that is psychologically soothing.

Judith: Yeah. And you know, which you ultimately want to do is you want to have your reader feel like they’re a part of that scene because if they’re a part of that scene, they are really into your book. And so that’s ultimately, I think what all of our goals are, sometimes it just takes a little longer to get there. So, but if you can do it, it’s fun. It really is.

Alessandra: Well, thank you both for joining us. We’ll put in the comment section, both of their websites, if you want to check them out.

Judith: Okay.

Alessandra: Fiona and Judith books. And if you miss the handout, that handout is also in the comment section, so you can download it there. So thank you both. This is First Draft Friday. If you enjoyed today’s chat, please check out our other chats at authors.ai. You can visit our First Draft Friday section. Or check out Marlowe who is artificial intelligence, like a developmental editor, she can read your entire manuscript in a matter of minutes and give her feedback. So please visit authors.ai, or join us for a future First Draft Friday. Thank you both again. And thank you to everyone who joined in today.

Judith: Thanks, guys.

Fiona: Bye.