I like to take inspiration for storytelling from all kinds of sources, not just books. Movies, paintings, dog walks: They can all spark an idea or solve a narrative problem giving me grief. But TV is often a bust. The need to sell advertising or hook viewers into an unending multi-series show often corrupts the purity of what should be a neat, defined tale with a beginning, middle and, most important of all, end (I’m looking at you, Snowpiercer).

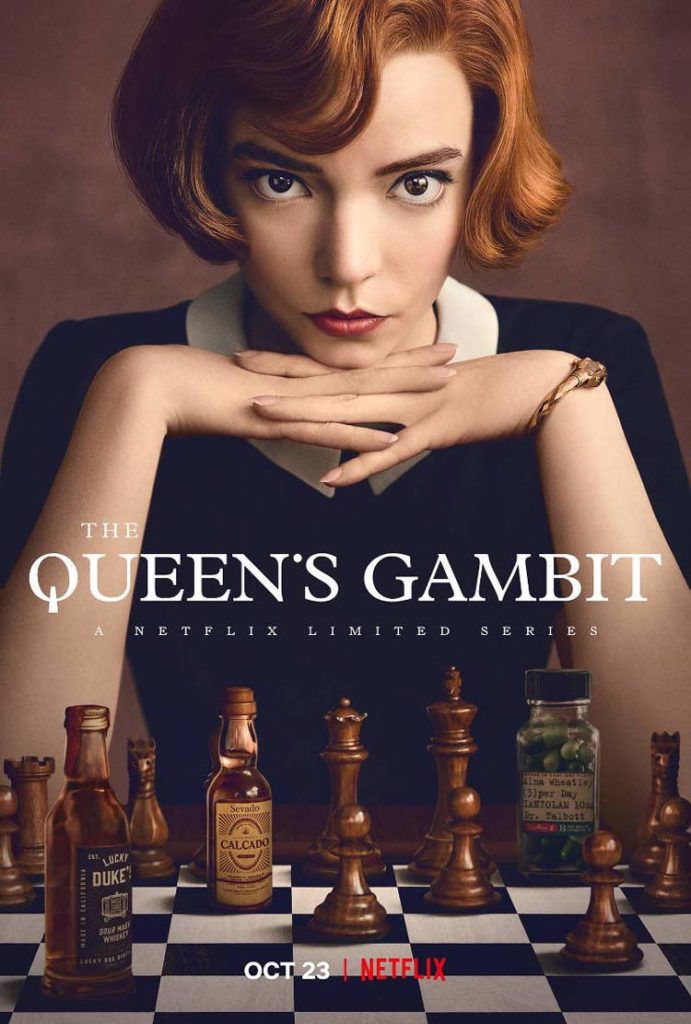

Which is why I want to talk about The Queen’s Gambit from Netflix. Adapted from the 1983 novel by Walter Tevis, it tells the story of Beth Harmon, an orphan possessed of a prodigious talent for chess.

Rather than give you a plot synopsis, which a) you won’t need if you’ve seen it and b) Wikipedia does it better, I want to share some insights about the show’s storytelling that, for me, lifted The Queen’s Gambit into a near-perfect piece of television drama.

(SPOILER ALERT: Yes, I am going to divulge key plot points, including the ending, so look away now if you don’t want to know what happens.)

How many dimensions does a great story need?

First, let’s deal with the central feature of the show: the chess games. I’ve played a few dozen games in my entire life. I know the rules, just about, and I can play a game without making a total idiot of myself. But is there a problem if another viewer doesn’t know the game? No. Because really, the story isn’t about chess at all.

Huh? But I thought…

Hold on. Yes, it’s named after a famous chess opening. Yes, Beth is a chess prodigy. Yes, all the action of the show revolves around chess games and chess tournaments.

But that’s because chess (or, to be more accurate, the world of chess) is the setting. Characters need to exist somewhere before they can undergo whatever trials you set before them.

The ancient Greeks liked to set their tales among sea voyages, battles and monsters. But their stories were really about family ties, loyalty, courage and the big existential questions, like what is the difference between gods and humans?

When we watch The Queen’s Gambit, we’re really watching a coming-of-age story. What the Germans call a Bildungsroman. How much of what makes us us is inherited? and how much is imposed on us? and how much, ultimately, is something we make for ourselves? There are sub-themes about what we need to get through life’s mill more or less in one piece, and whether artificial aids – alcohol and drugs in Beth’s case – are a better solution than friendship and self-reliance.

My first takeaway

So my first takeaway is that when you embark on a story, get it clear in your own head what, exactly, the story is that you’re telling. There’s nothing wrong with having a novel that focuses on the rise of a super-talented chess player, any more than there is of a footballer, a ballet dancer or a stonemason. But if that’s all there is, your story is going to be one-dimensional, or at most two.

She plays a match. Will she win? Yes? Or no? She enters a tournament. She’s going to win it or she’s not. And so on. You leave the reader with only two options for every challenge and nothing else to focus on. If Beth’s only challenge was her opponent in each game, the show wouldn’t have been nearly as interesting.

What made The Queen’s Gambit such a great piece of storytelling was that the reasons why Beth might have won or lost each game, each tournament, were rooted in factors outside her own technical abilities as a player. She has a mile-wide streak of self-destructiveness for a start, and one of the best aspects of the show was the way the writers kept you off-guard about how, when and if this streak was going to kick in. Voilà! The third dimension: the lead character’s inner world.

How to dramatize drying paint

Continuing with the big themes of the show, we have those chess games. From watching the show, it would seem that chess is a spectator sport. Who knew! Personally, I have some drying paint I need to go check on. From reading reviews of Tevis’s novel, rather than the Netflix adaptation, it seems that the book dives much deeper into the individual games Beth plays, seemingly with move-by-move narratives using proper chess notation.

That would have been death on screen and wisely, the director opted to focus on the action of the games, rather than the motion. This is one of my guiding ideas as a novelist and I wish I could claim credit for it.

Formulated as Don’t mistake motion for action, it’s been widely attributed to Ernest Hemingway. It seems that, like all those vaguely Zen-sounding quotes attributed to the Buddha, Hemingway never actually said it. According to Marlene Dietrich, Hemingway told her, ‘‘Never confuse movement with action.’’

Attribution aside, what does it mean for us? Well, look at the way the director shoots the many chess games in The Queen’s Gambit. Two players face off across a chess board. Their eyes lock. One looks cocky, one calm. One a typical preppy white guy, the other a flame-haired ‘‘weird’’ looking girl (of all things!).

She slaps down the button on the clock to start his time and we’re off. Into the middle of a gladiatorial contest. It’s not what the moves are that matters, but the way they’re made. Pieces are shoved, slapped, nudged, snatched and toppled by hands that grasp, tremble, hesitate, flutter. We can see into the players’ minds, and hearts, by the way they play.

As the show moves on, we often see the games through a recurring metaphor of a ‘‘ghost game’’ playing out on the ceiling that Beth, with tranquilizer-enhanced visualization skills, uses to navigate her way to victory. (Usually.)

In a bravura extended sequence of games at the Moscow Invitation tournament that comprises the show’s finale, we see progressively less of each game. An opening handshake and a closing bow, wobbling lower lip, bow or smile signal defeat and victory for Beth. As the last few games whirl by, we just see her leaving through a crowd that grows in size and enthusiasm for the glamorous young American. They’re cheering and calling out ‘‘Liza’’ and we know she’s won again.

My second takeaway

My second takeaway is be alert to the possibility of economy in your storytelling. The first time your lead character engages in something they do well, a fistfight, perhaps, or an ice carving, yes, by all means, show us every last detail. But if this is a repeated scene, then consider showing us what it means, rather than simply what happens.

I’ll give you an example. I write police procedurals set in the U.K. In Britain, when a cop arrests someone they recite ‘‘the arrest script.’’ It goes, in full, like this:

Joe Schmoe, I am arresting you on suspicion of the murder of Mrs. Schmoe. We have evidence linking you to the crime. You do not have to say anything but it may harm your defense if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. Anything you do say may be given in evidence. Do you understand?

It’s a great piece of theater and a way for us crime writers to show off a little. (Hey! I know a police officer. Or, more likely, I went online and Googled it.) But including it more than once risks turning off your reader. ‘‘Yeah, yeah,’’ they say, ‘‘we get it already, he’s arresting the suspect.’’ And they skip over it.

Now, you might argue that it doesn’t matter if a reader skips a bit they find boring. But my worry is that once they get the skipping habit, it’s easier for them to keep skipping. And that fatally weakens the bond I’ve established between me and my reader. No, scratch that, between my lead character and their reader. Elmore Leonard said it best: ‘‘Try to leave out the part that readers tend to skip.’’

How do I solve this little conundrum in my books? I say, ‘‘Inspector Ford recited the arrest script and waited to see how Schmoe would react.’’ Because it’s the reaction that’s interesting, not the recitation.

‘You’ll never get away with this … Ooh, look! A butterfly’

During the course of the show’s seven episodes, Beth grows up. She starts as a little girl and ends as a young woman. In fact, she doesn’t just grow up, she matures and, by the end, has overcome not only the challenges of the game but also her personal demons.

None of it was rushed, everything was given its fair share of screen time. We see her go from making her very first move, in the basement of the Methuen children’s home, where she pitches up after her mother commits suicide (in a car, with Beth in the back seat), to beating her nemesis – the Soviet, Borgov – on his home territory.

Along the way, she descends into her own personal slough of despondency, furnished with liberal amounts of booze and pills, which from the period setting and color of the pills I’d guess would have been Librium.

That’s a lot to pack into five and a quarter hours of TV. The writers and directors managed it by keeping the spotlight firmly on Beth. She’s in virtually every scene – the POV character throughout – and even when she isn’t physically present, she’s on the other end of a phone line or the subject of the conversation.

Having this limited third-person viewpoint is a really good way of maintaining your own narrative focus as a novelist. You don’t have to do it, and I freely use other styles of storytelling as when I need to, but I have found that it’s easier to tell a tight tale when you restrict the number of viewpoints (ideally to one).

The point for me where I really saw the writer/director pull on the reins was in the final episode. Beth approaches the State Department for financial help getting to Moscow. They can’t help, or not at such short notice, but they do send a minder to accompany her on the trip.

At one point, in a car, Beth turns to him and asks, ‘‘What part of the State Department are you with, exactly?’’ He offers nothing more than a laconic smile as if to say, ‘‘Really?’’ We have him pegged as CIA and his role becomes clearer when he tells Beth that Borgov, who travels internationally with two KGB minders of his own, might try to approach her or send her a message.

I thought we were about witness a late-stage narrative distraction as a defection subplot ground into gear. But no, the only message Borgov sent was via some superbly minimalist face-acting, in which a clenched jaw muscle, or a nervy glance at the ceiling (remember Beth’s invisible matches?), revealed his state of mind.

My final takeaway

My final takeaway is to stay true to your story. If it’s girl-meets-boy, and girl is an international woman of mystery, that’s fine. But I’d advise you not to stray too far into the details of her current mission. It’s background, it’s more setting. This is a love story. That’s where you should focus your creative energies.

On the other hand, if you’re writing a murder mystery, keep your main character locked on to solving the crime. Sure, give him a love interest, but make sure that this B story relates closely to the A story. Maybe he’s spending time with his new squeeze when he should have been safeguarding a crucial witness, who’s now gone missing.

It’s all about the story

For me, The Queen’s Gambit was one of the best pieces of on-screen storytelling I’ve ever watched. It has its detractors, of course, but the overwhelming reaction, from critics and viewers alike, has been hugely positive. I’d suggest that one of the reasons, leaving aside the drop-dead gorgeous production design, costumes, makeup, period details yada yada yada, is the sheer quality of the storytelling.

And if you need a little help with your own storytelling, determining what your story appears to be about from the reader’s perspective for example, why not try out the Authors A.I. fiction-savvy bot, Marlowe?

It’s your move.

GET FREE A.I. REPORTS