Ask a roomful of readers to list the aspects of a book that they think are the most important and most will hit you with plot, action and dialogue straightaway.

They’re not wrong. Those things are important. But without a vividly evoked sense of place, they exist in a vacuum.

A sweet Regency romance that takes place in an 18th century Bath that’s indistinguishable from a 20th century Bristol won’t tug the reader’s heartstrings as firmly as it could. That New Orleans-set voodoo mystery won’t send shivers down the spine if the reader feels she could just as easily be in New York or New Delhi.

It’s sense of place that roots your characters in the world you’ve created for them. Sense of place that gives them a home, a workplace, a setting for whatever struggles and challenges you intend to confront them with. Sense of place that, done well, helps your location become a character in its own right.

Photo by Cajeo Zhang on Unsplash

Why is a sense of place so important?

Sense of place is the feeling your readers get as they read your novel that they have left their place behind and entered yours. It’s a transporting feeling that makes the world of the book they hold in their hands as real, if not more so, than their own.

It was the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge who coined the phrase, suspension of disbelief, that willingness on the part of a reader to accept as real something palpably unreal. Without it, reading a novel is a profoundly unsatisfying experience, as we are always aware that this is precisely what we are doing.

Sense of place, done well, helps the readers suspend their disbelief. You’ll reap the benefits in two ways. Glowing reviews that, even if they don’t specifically mention your magnificent way with sense of place, nonetheless praise the realism of your book and the way they were caught up in your characters’ lives. And more sales. Always good.

Seven aspects of sense of place you must consider

So, what goes into a sense of place? Here is a seven-point checklist. It’s not exhaustive, but as you work through it, you will see other things you can add to your own expanded version.

Photo by Madeleine Ragsdale on Unsplash

1 Climate and weather

Now, I’m not going to suggest you start your book, ‘‘It was a dark and stormy night…’’

How about this?: ‘‘Flinching at the thunderclaps, Paul looked up into the lightning-crazed sky, fat raindrops, white in the moonlight, blending with his tears.’’

Obviously, weather can serve as a metaphor, as in my slightly tongue-in-cheek example above. But it can also make life easy, or difficult, for your characters. If it’s humid, they’re going to sweat and feel uncomfortable. If it’s perpetually foggy, they won’t be able to see very far. If it’s sub-zero they’re going to be rushing from one heated building to the next. Or fearing a slow painful death outdoors from hypothermia.

I set one of my Stella Cole crime novels in Sweden at the time of Midsommar. The seemingly endless daylight served to disorientate her as she hunted down a serial killer.

2 Geography

Yes, where does your story take place? A city, a rural location, a mountain wilderness, a steaming jungle, a desert? What are the big features that define it?

Is there a thundering river that makes conversation impossible? Does it wash things away, but also bring them into the center of town? Is there an interstate that offers a way out, but also a route in for unsavory characters?

These big features of the landscape – whether natural or artificial – are a quick way to fix a location in your reader’s mind.

3 Architecture

When describing buildings, remember to see them the way a painter would. A New Orleans bordello might have blue and pink paint and wrought-iron balconies. But what sort of condition is that paint in? Scabbed and flaking? Pristine and fresh-smelling?

Are the balconies gleaming with newly applied black paint or rusting half-through and in danger of detaching from the wall and pitching the hookers into the teeming street below?

Also, resist the temptation to focus only on the tourist spots. If your book is set in Manhattan, by all means go to town on the gleaming metal crown of the Chrysler building, but also show us graffitied brownstones and neon-lit subway entrances.

4 Street furniture

Dropping down another level, you can build what one of my editors, Jack Butler, calls the ‘‘grain’’ of a place by describing its incidental features. Road signs, street lamps, trash bins, bus stops, fast food carts, walk-don’t walk signs, manhole covers, patched blacktop, mailboxes. The 1,001 everyday objects so commonplace we never notice them but which, when described by a writer, can help define a place.

5 Flora and fauna

Depending on the time of year, which also has an impact on your reader’s perception of place, you might have trees, shrubs, flowering plants, weeds, moss, ferns to work with. Are the trees in bloom or dropping their leaves? Do the flowers have a smell? Are gardens well-tended or reverting to wildness?

How about the creatures that live alongside the human beings in your story? In one of my books, the opening sentence reads thus:

My name is Art Zeffer and I live in a part of the Windy City where even the rats have concealed carry licences.

Those rats are metaphorical, but yours might swarm in deserted tenements or over babies’ sleeping forms. Or do you have a plague of unicorns in your fantasy novel, or man-eating crocodiles? Swarms of biting flies that drive the characters half-mad? Tell us!

6 Vehicles

As a rookie novelist I used to put far too much effort into describing cars. Now I try a lot harder to use a light touch. But cars, particularly in American-set novels, can do an awful lot of heavy lifting.

They can be status symbols – a dentist’s Porsche; social signifiers – a redneck’s pickup; menacing – George Stark’s jacked-up Oldsmobile Toronado in Steven King’s The Dark Half. Or they can simply locate the action in a particular era: think those bulbous 1940s autos in a lot of hard-boiled P.I. books, sleek sixties coupes or proton-drive personal transportation units in a sci-fi novel.

7 Objects

In a row of identical terrace houses, the interiors will be as different as the exteriors are all clones. They reflect their owners’ personalities. Have fun filling your character’s home with furniture, pictures, plants, tchotchkes, children’s toys – or their absence – gadgets and gizmos, cookware, power tools, hobby equipment.

And remember, it’s not so much the presence of these things that sets up a sense of place at this most domestic of levels, as their type, style and condition. Three different people might have a fish tank in their lounge. One might be green with algae, another bright with jewelled fish, the third home to a severed head.

‘But I live in Des Moines!’

How are you going to research your chosen location? Back in that period of prehistory that ended roundabout 1993 when the Web came along, if you wanted to know what, say, Casablanca was like – really like, I mean – you had to go there.

Writers like Hemingway and Graham Greene would make a point of hanging out in Havana or mooching around Madrid, imbibing the atmosphere alongside the local hooch.

Or did you? Shakespeare didn’t visit a remote tropical island before writing The Tempest. Bram Stoker stayed at home while conjuring up Dracula’s Transylvania. And I am certain Ursula K. LeGuin did not first fly into space before embarking on her glittering career as a science fiction author.

How did they manage it, then? Well, they used their imagination.

Travel …

However, there are a few things we can do to ensure we capture the spirit of a place. Travel is still an option. But it’s rare we have the budget solely for research trips, so it tends to be a case of borrowing details from our vacations or setting our novels in places to which we have already traveled.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

… or befriend a traveler

If I happen to know one of my friends is off on an exotic trip, I’ll ask her to record a few impressions for me. Back when I was still writing copy for a living, I discovered a client was going to be in Hong Kong. I asked her, specifically, to tell me about any sounds and smells that she noticed.

She came back to me with the slap-slap of plimsolls on hot pavements, the clock-clock of bamboo scaffolding poles and the fermented fish/blue-cheese smell of stinky tofu (that’s what it’s called).

Google Street View

Google Street View is probably my most-used Web resource after Wikipedia. I have stood outside the gates of the British embassy in Tehran, noted down the signs on the gates of the MI6 building in London’s Vauxhall, and hung around outside a beautiful colonial-era hotel in Vientiane.

What GSV does so well, is show you the incidental details. The clothes worn by passersby on a Gaborone street. The uniform of the gate guards at that embassy in Iran. The color of the roses in a Stockholm park. The profusion of mopeds in downtown Phnom Penh.

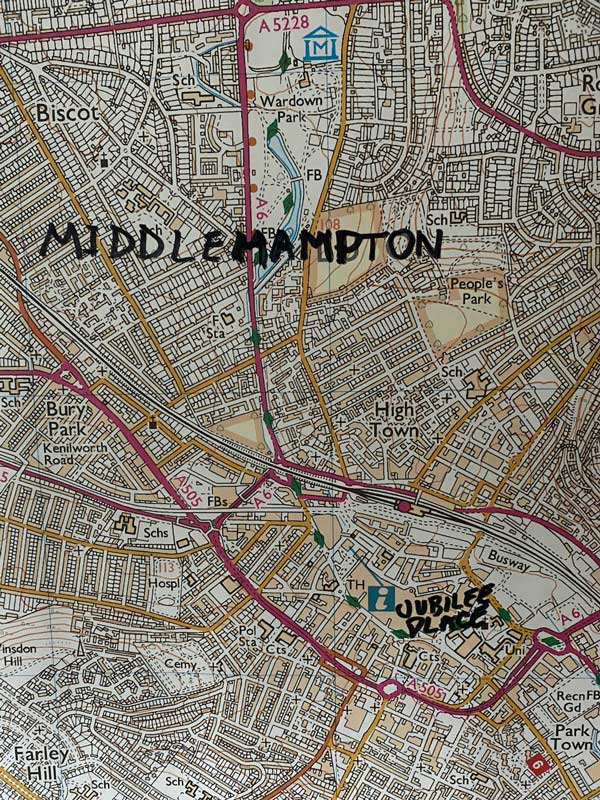

Draw a map

If you are setting your book in a made-up place, it might help to draw a map, or adapt an existing one.

That way, you can, at the very least, ensure that neighborhoods or places relate to each other consistently. You can get directions right and position things like rivers, town boundaries, woods and factories where you want them to be.

How to write it: five practical tips

1 Try not to interrupt the flow of your story while you pause to set the scene.

It’s much smoother and more enjoyable for your reader if you weave the details of place into the action of your story.

So, rather than write, ‘‘Carcassonne’s origins as a medieval fortress-town were clear in the turrets and crenelations that fringed its wall. Narrow streets wound upwards from the main entrance, their cobbles worn smooth by many millions of feet,’’ you could go with ‘‘Rosita felt the narrow alley as a constricting corset, hemming her in as she tried to escape her pursuers, who knew the medieval fortress better than she ever would, from its turrets and crenellated walls to its slippery cobblestoned streets.’’

2 Use all the senses, especially sound and smell.

Not just a tip for sense of place, but it really helps if you write beyond the visual. Like I did in Hong Kong, describe what a character smells as they walk past a fast-food joint. Or how the air feels on their skin.

Are the handrails in a subway station greasy and warm or cold and clinical? As the air rushes into the station ahead of the train, does it bring swirling grit and tumbling litter?

3 Zoom in

It’s tempting to give the reader the big picture. A mountain. A forest. An entire city. A sweeping desert. But go in close – real close – and show them something in such pinpoint detail that they could only see it if they were actually there with the character.

In my thriller Rattlesnake, much of the opening action takes place in the Chihuahuan desert in Texas. Here’s how I described it in one scene.

As he scanned the glittering crust in front of him, he began to notice smaller and smaller elements of the picture. A large, black ant dragging a dead beetle towards a dime-sized hole. A triangle of mica flakes, twinkling like diamonds. A cactus spine, detached from its parent plant and now resting on the sand like a miniature yellow javelin.

As a result, I received a very nice email from a reader who said he’d camped in the Chihuahuan desert and knew the place I was talking about. That accuracy helped him believe in the scenes set someplace he didn’t know: the killing fields of Cambodia. Job done!

4 Zoom out

Unless you want your reader to spend the entire book with their nose in the dirt, you’re going to have to pull back at some point. Give them a medium shot and then a wide shot to take them from the micro-details to the broad sweep of the place. Here’s how I did it in that same scene.

Despite his intentions to stay focused on the place where Vinnie might have fallen, the view of the distant mountains was too beautiful to resist. He lifted his head a little to take in their misty, purple-grey serrations. Between his current position and the range of peaks, nothing but empty desert.

5 Movement in landscape

I share this tip with you courtesy of my friend and first editor, Tom Bromley. Tom is an excellent writing coach and teaches at the Faber Academy. In writing about the landscape, Tom suggests we include movement.

Slender trees, poplars or cypresses, perhaps, might wave in the wind. A flock of sheep, rather than just standing still, might track left to right across a field. Thunderheads might boil up to the south or spill their freight on the land in shifting charcoal smears between sky and earth.

The place where it all happens

Whether you’re writing a fantasy novel or a cozy mystery, a bad-boy biker romance or a vigilante thriller, the action takes place in a location. Try to make that location a somewhere, not an anywhere. Do your research if it’s a real place, and use my checklist if it helps with a made-up place.

Keep things to a human scale, too. A lake might be 50 miles across, but your hero is paddling into the future from this dock, on this bit of the shore, under this sky.