I stared at the email I had just composed. Wondering whether I had the courage to send it. My finger hovered over the mouse.

The cursor alighted on the send button like a fly on a branch occupied by a chameleon. My heart beat just that little bit faster. I swallowed. Clicked. Sighed.

I had just sent the final version of my latest thriller, Three Kingdoms, off to be analysed by Marlowe, the new artificial analysis from Authors A.I.

It’s an odd thing. To feel you are a good writer but then to submit your work to a machine that doesn’t know you, doesn’t care about you, isn’t paid by you and has no axe to grind. She’s just gonna do what a bot has to do. Count stuff and measure it against other stuff.

I deliberately chose my most recent book. It’s the tenth in a series and I was hopeful of a pat on the back from Marlowe. But you never know. The Amazon reviews were virtually all 4 or 5 stars. My beta readers, ARC, editor and proofreader had all praised it. So why was I nervous?

Would there be a ticker-tape parade?

Writers tend to be angsty types, I think. The kind of people who wake up at 3 a.m. worrying about things. Relaxation doesn’t always come easily. So having a cold, inhuman machine assessing my novel against the best of the best filled me with a mixture of dread and interest.

Obviously, I hoped it would be all green ticks, gold stars and ticker-tape. But what if…

What if she didn’t like it? What if it stacked up against my heroes like a water pistol against a Glock 17? What if it was a solid C when I wanted an A+?

I made myself a cup of coffee and settled in for the wait. Which proved to be surprisingly, mercifully brief.

In under an hour, an email pinged into my in-box with my report. I took a comforting swig of coffee (wondering as I did so whether what I really needed at this point was more caffeine) and began skimming.

And you know what? It was fine. I relaxed and started to read properly. And it was fascinating. I feel I have a working grasp of what makes a good thriller, plus an instinctive feel for language, honed over the last half-century including 30 years as a copywriter. But there’s something about seeing that intuition confirmed in terms of data that’s reassuring.

It wasn’t all ticks, however. There were a few places where I saw how I could improve. And what’s so brilliant about Marlowe is she gives you the specifics.

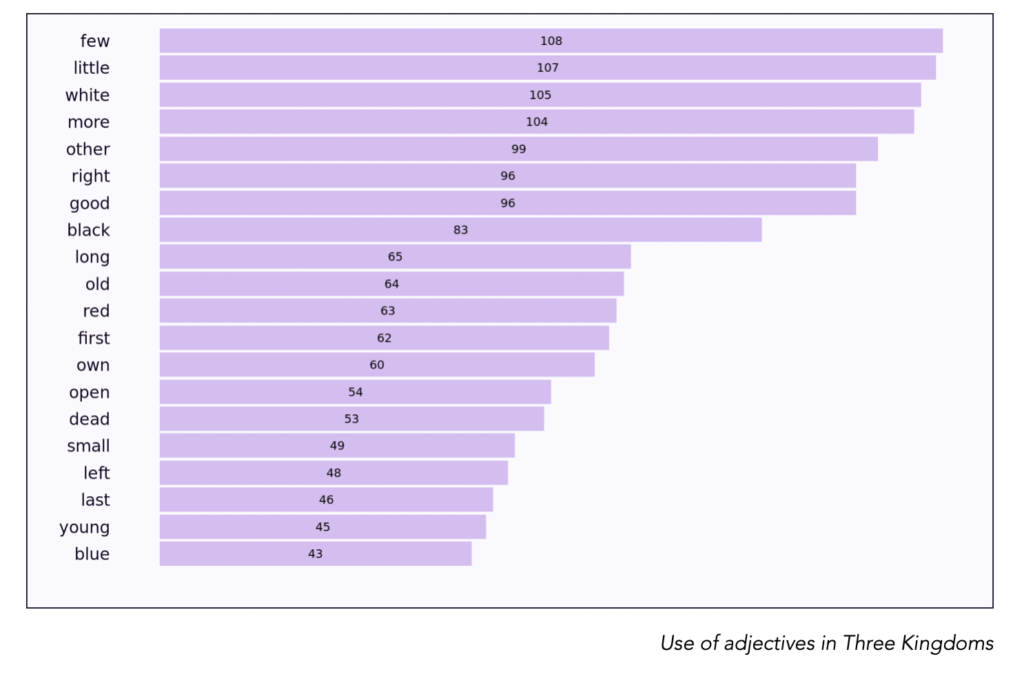

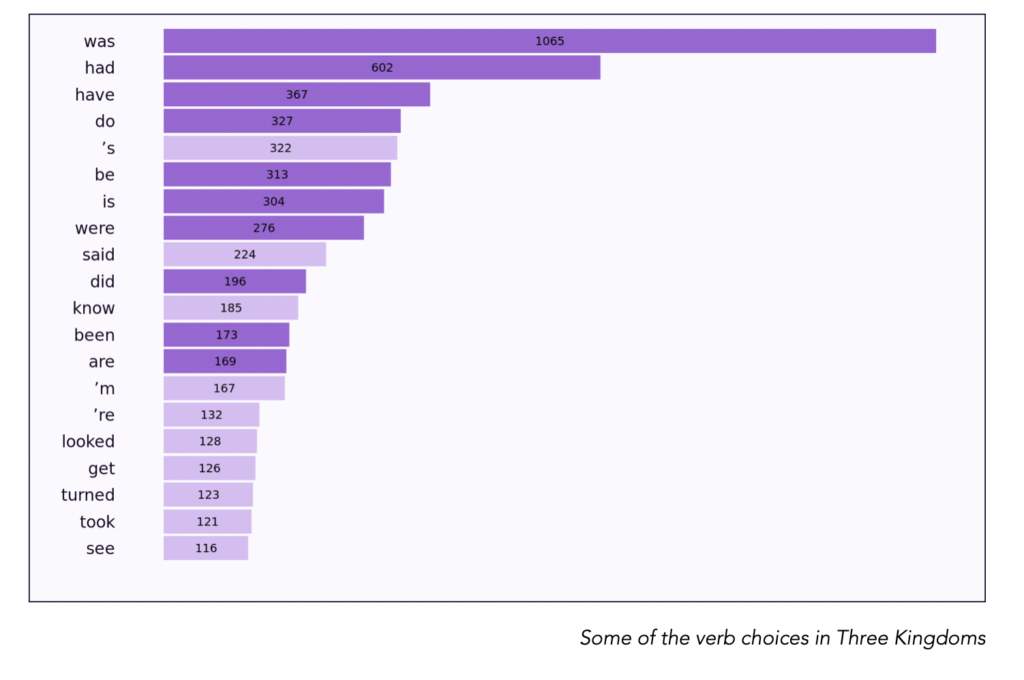

Not just, “it has a sagging middle” or “you could use a few less adjectives.” But you could do with an action beat between here and here. Or, these are the adjectives (and adverbs) you use the most. Do you really want to use “very” that many times?

So here are the charts and my interpretation of what they mean.

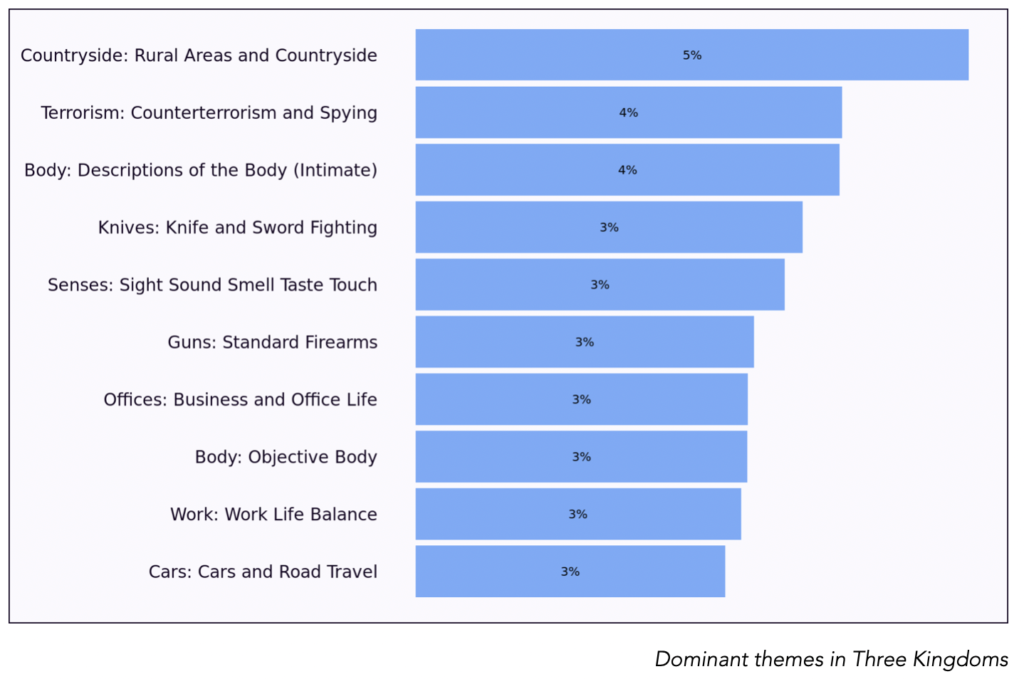

Dominant themes — rural terrorism?

It’s an action thriller, so having terrorism and physicality plus weapons prominent made sense to me. The countryside one was weird until I realised there was a lot of the action set in rural China and Kazakhstan. However, in retrospect, maybe I could have cut some of this description in favour of action. (You’ll see how this dovetails into other parts of the report in a moment.)

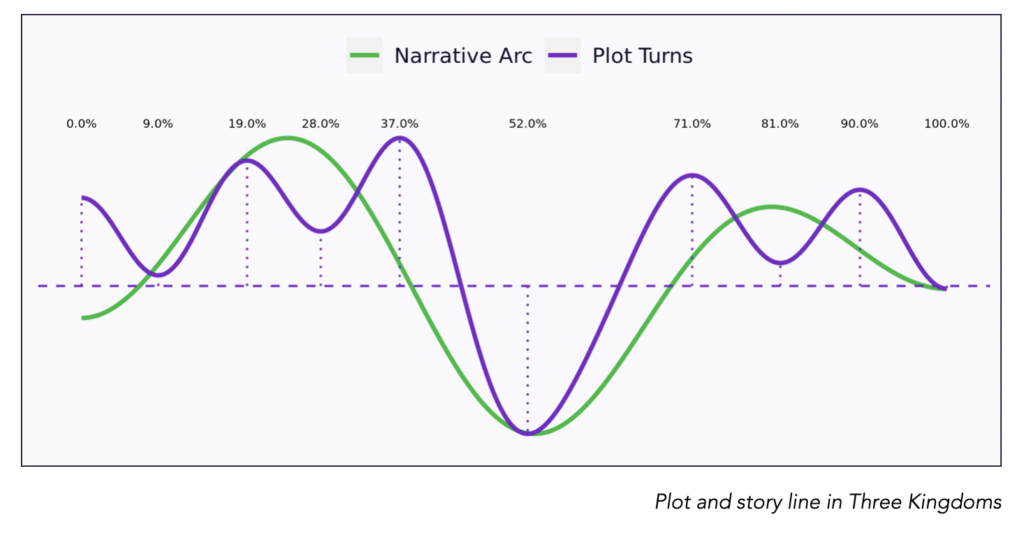

Plot and storyline — needs something at 50%!

The green line represents the overall shape of the narrative. The purple, how the plot moves within it, based on events and action scenes. Above the dotted line means the emotion/action is positive, below, negative. So, a character dying would be below the line, a character triumphing over an adversary, above it.

You can see from the green line that Three Kingdoms follows a classic three-act structure. In the first third, the hero embarks on his mission and things, broadly, go well. In the middle third, he experiences setbacks. In the final third, he overcomes his enemies and achieves his goals.

But look at the portion between 37% and 71% of the story. Nothing wrong with the dip below the line. But in this third, there is only a single plot turn. Looking back, I can see that, had I seen this at the writing stage, I might have added a turn at the halfway point.

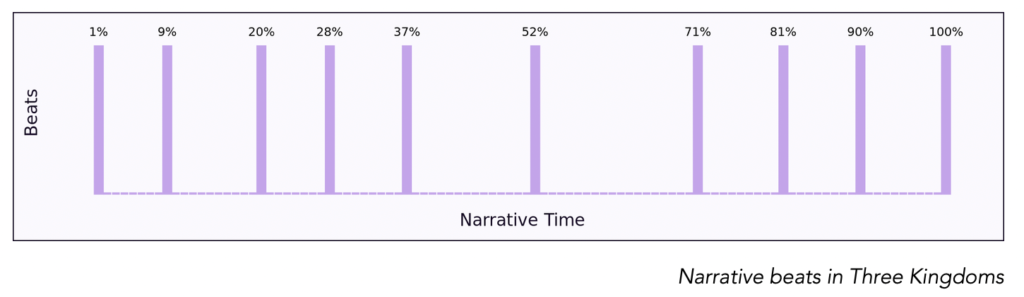

Can you feel the beat?

This chart takes the purple curve from the one above and simplifies it into a time-stamped metronome of the novel’s beats. They come roughly every tenth, apart from that gap between 52% and 71%. A bar fight, an argument, a hunt or a switch to the enemy’s POV could all have done the job. I sense a thumbs up from Marlowe.

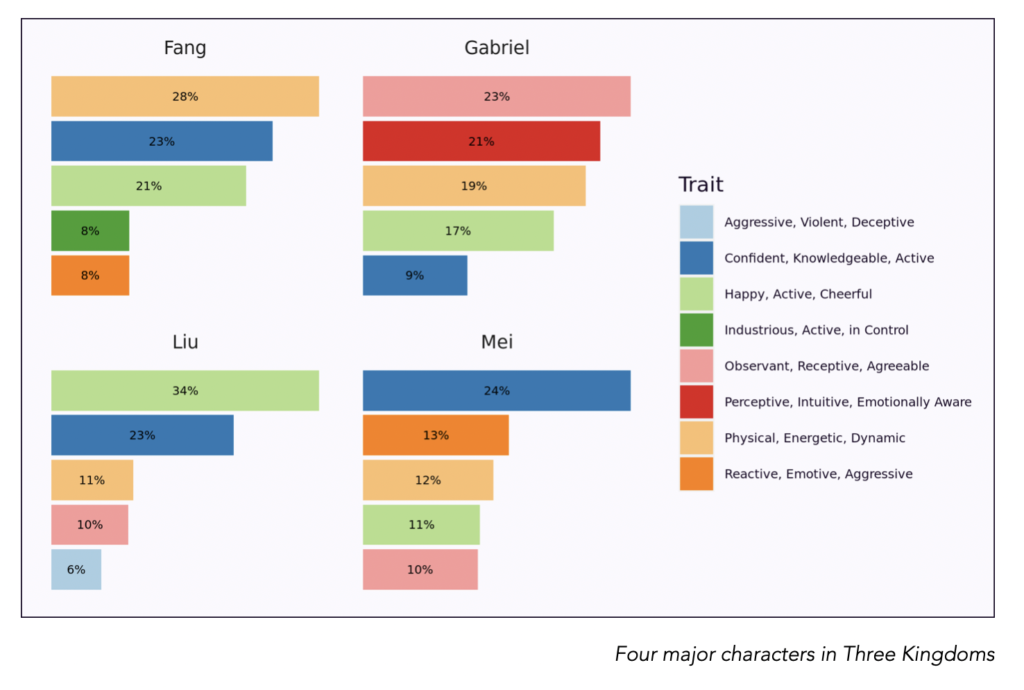

A mark of character

In some ways, this was the most interesting chart. It shows how my four main characters measure up in terms of their traits on the page. And that’s an important qualification.

Because in my mind they might have been all sorts of things. But on the page, which is the only place my readers will see them, this is what they are really like.

And it’s fine. Fang is enemy No. 1. A Triad boss. I nailed him. Gabriel is the hero. An ex-SAS member who is quite ready to kill but at his core is driven by honour, duty and compassion. (Thank you, editors, for allowing me the British spelling of honour.)

Liu is a Communist Party official who double-crosses Gabriel. Perhaps because he acts mostly via dialogue, his character is the least strongly drawn in terms of the good-evil axis. On a rewrite, I would have worked in him more to dial up the deception.

Mei is Gabriel’s sister. And Fang’s enforcer. She’s perfect. I’m really happy with how Marlowe sees her.

Talk about action!

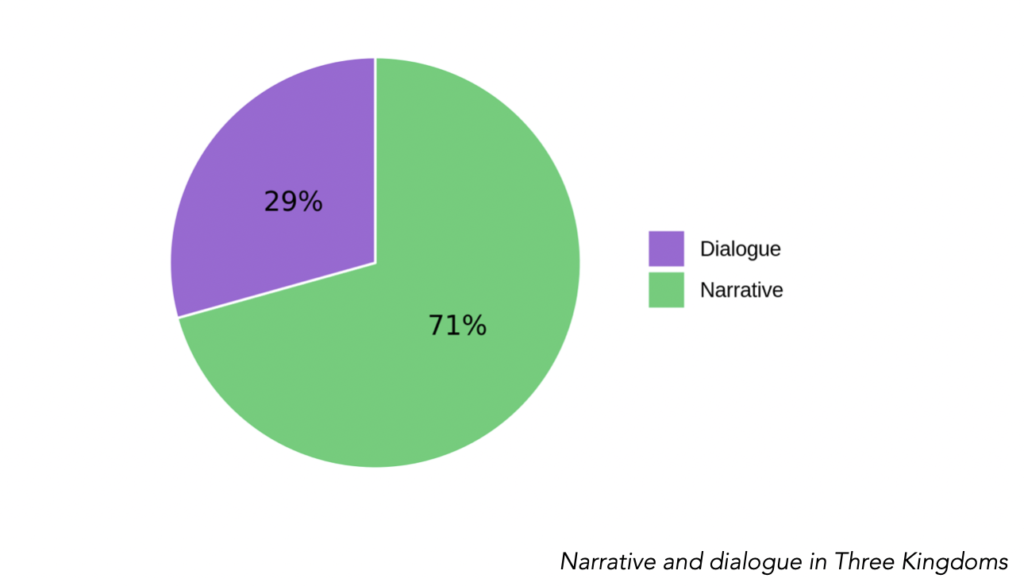

According to Marlowe, in my genre, the most successful authors have between 25% and 35% dialogue. I am happy. Interestingly, there is a big spike in narrative versus dialogue slap-bang in the middle of the book, where the action droops a little. I wonder now whether including more dialogue would have helped with the pacing.

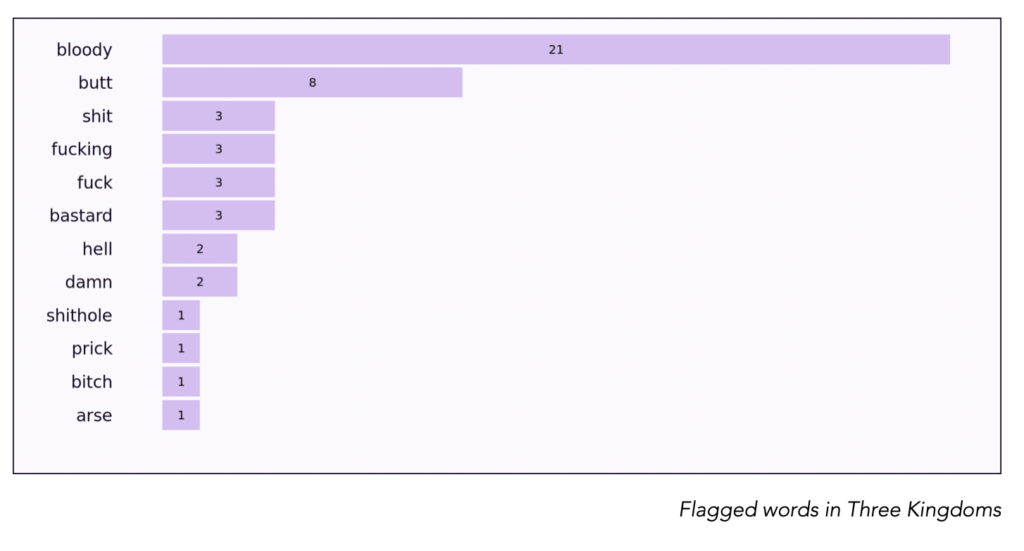

Potty mouth? Me?

Well, the bluenoses might still be calling for the smelling salts but this is OK, I think, for a paramilitary thriller. It’s still only 0.05% profanity for the book as a whole, and “bloody” is a relatively benign cuss-word. Would I change it? No. My readers know what to expect. Though I have toned it down as the series has progressed. No sense in deliberately alienating more sensitive readers who are also my customers.

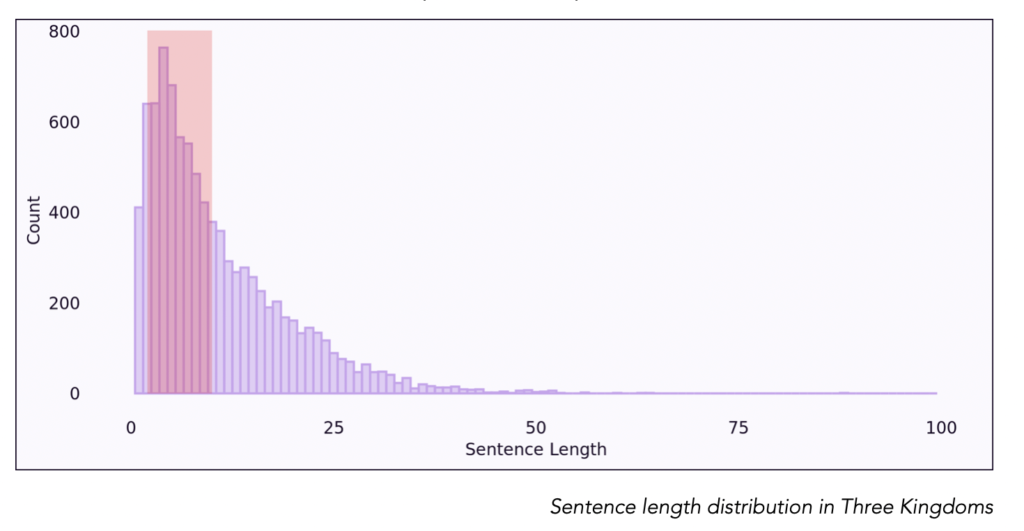

How long is too long?

Marlowe tells me that successful authors of popular fiction concentrate the bulk of their sentences in the 2-10 words range. My average sentence is 10.71 words. In terms of complexity, Marlowe tells me successful popular fiction scores between 2 and 3. I get 2.58. I am sure my training as a copywriter helps me write short, crisp sentences. Like this.

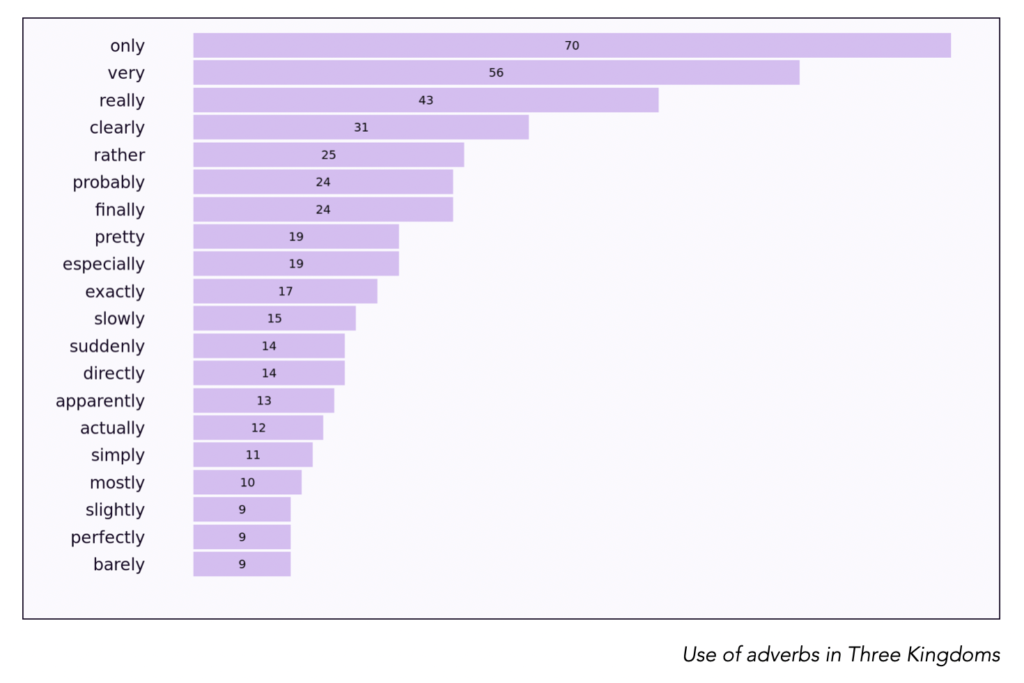

The language of style

These final three charts map my use of adverbs and adjectives and potentially passive verb constructions. All to be kept to a minimum. This is where Marlowe swaps her dev editor’s hat for a copy editor’s green eyeshade.

I try to use strong and precise nouns and verbs – “clattered” rather than “fell noisily,” a “colossus” rather than a “very big man” – but a little help from a dispassionate A.I. is always welcome.

Yes, a ‘robot’ can help me write better fiction

Having read, and re-read, Marlowe’s report on Three Kingdoms, I realised two things. One, my gut feel was pretty much on the money. My books are in the same ballpark, and sometimes on the same team, as the best-in-class authors I aspire to match in terms of quality (and sales).

And two, without once saying anything subjective — “I liked this bit” and “I didn’t like this bit” are about as much help to an author as a blunt pencil — Marlowe gave me absolutely concrete, actionable insights into the text. If I were sending her a pre-publication draft, I would definitely have worked on it one more time.

Will I be sending her my next work in progress? You better believe it.

Check out Authors A.I. and compare author plans.

GET FREE A.I. REPORTS